The Science of Habits: Training your Mind

- Ananya

- Aug 27, 2023

- 4 min read

It’s believed that on average, it takes about 2 months before a behavior grows into a habit. Until I started working on this post, as someone who is constantly trying to optimize my routine and to improve my productivity, I was rather discouraged by this kind of data. However, I’ve come to find out that habits are deeply powerful, such that if you understand the science behind habit formation, you can actively empower yourself with that science to form your desired habits. Habits shape our daily routine, influence our behaviors, and have a profound impact on our overall well-being. There’s some habits that seem so hard to break, while others seem almost effortless. Some of these we don’t even remember trying to create, like the pocket you slip your phone into or the first thing you do when you wake up. No matter how elusive a habit may seem, with science it’s relatively easy to both form and change habits. Today, we learn how we can use science to change our habits to achieve our own goals.

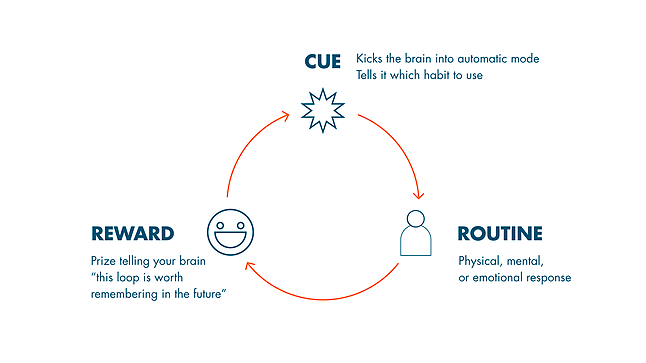

A concept called the “habit loop” was first popularized by Charles Duhigg in his book, the “Power of Habit”. The habit loop consists of three stages: the cue, the routine, and the reward. If you’re reading this and it seems to ‘ring a bell’, that’s because this is directly related to Pavlov’s experiments! Pun intended. The cue is the trigger that initiates the habits (in Pavlov’s case, this would be ringing a bell), the routine is the behavior itself (salivating or a sudden feeling of hunger) and the reward is the positive outcome we receive from completing the habit (the food).

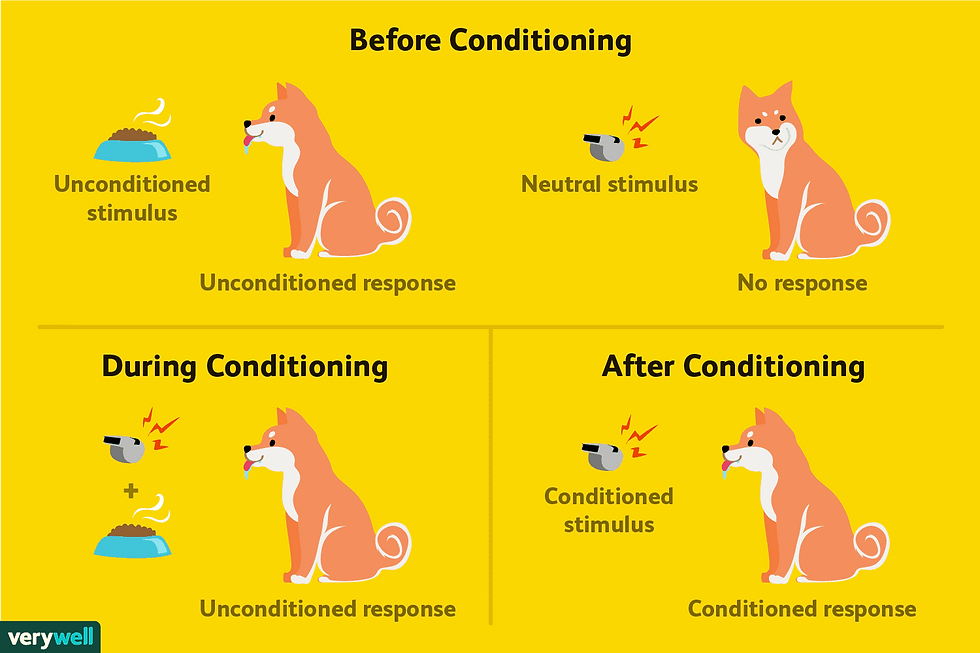

If you’ve ever taken a psychology course, you know that Pavlov won a Nobel Prize for this research on classical conditioning (in his case, more specifically on digestion) where after habitually providing dogs with food paired with the ringing of the bell, overtime, the dogs began salivating at the sound of the bell. By understanding this loop, we gain insight into how habits are formed and how we can use it to our advantage in training our minds for success.

In classical conditioning, you have a stimulus (food) paired with another stimulus (bell) to elicit the desired response (salivating). Over time, you’ll be able to remove the initial stimulus and just have the additional stimulus elicit the response. But, what does a dog’s salivating habits have to do with you? This form of classical conditioning is the starting point to understanding habits and automatic behaviors. For example, assume you don’t have any food at home for breakfast except cereal and milk. You can be conditioned to eat this cereal for breakfast every single day. At first, your stimulus will be the sight of the milk and cereal, with your additional stimulus being your hunger, resulting in the response of eating milk and cereal. Until eventually, every morning when you wake up, without even the sight of the cereal, the additional stimulus of hunger is enough to create this new breakfast habit.

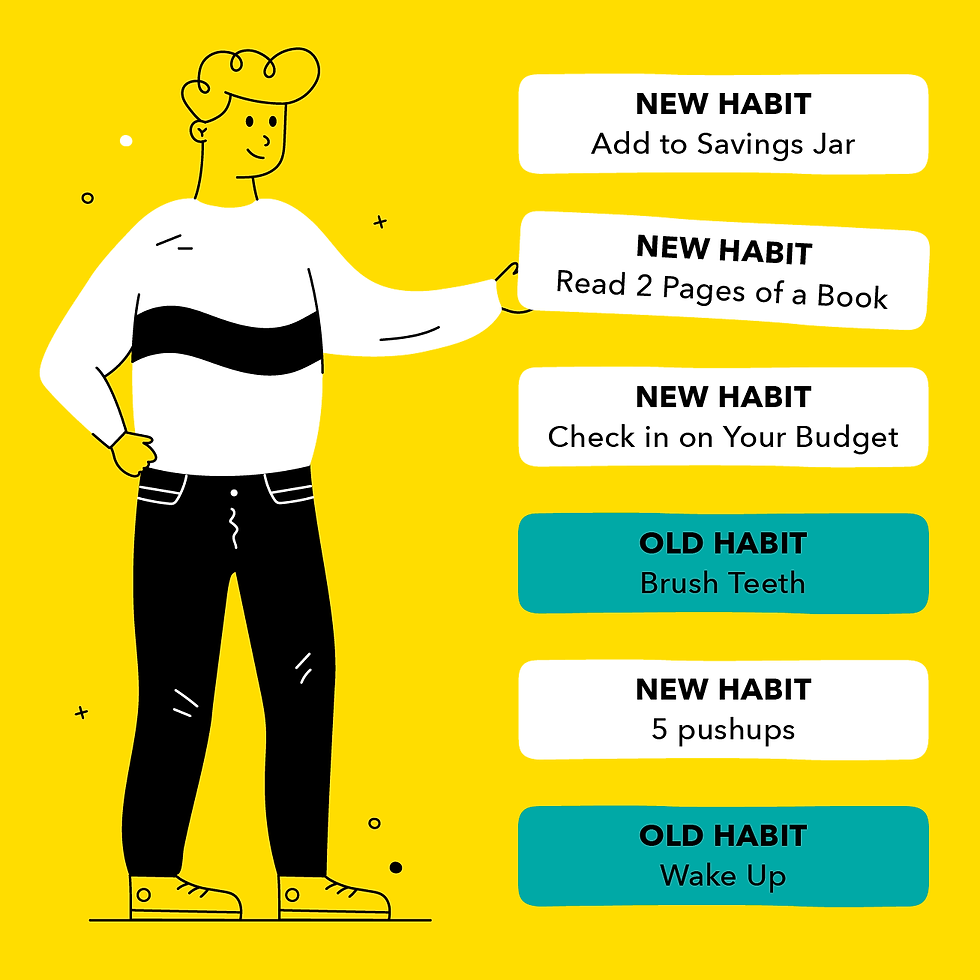

In addition to this type of conditioning, we can harness the power of habit stacking. Habit stacking is a dynamic technique that allows us to piggyback new habits onto existing ones. By linking a new habit into an established routine, we increase the likelihood of its success. For example, if you want to incorporate meditation into your daily life, you could stack it into your hypothetical habit of making yourself a smoothie every morning by meditating for a few minutes before. With habit stacking, you attain the kind of consistency that is essential to solidifying habits. Engage in your chosen behavior regularly, even if it's in small increments. Over time, these actions will become ingrained in your daily routine, and the habit loop will solidify.

Keeping this original research in mind, let’s explore what we know about creating and changing habits. First off, remember that a small and specific habit goal is far more attainable than a vague one like “I’m going to exercise more”. Rather, frame it into a more concise and specific agenda, such as “Before I head to work, I’m going to go on a 30-minute run” or “After I get home, I’m going to change into my athletic wear and run on the treadmill for x minutes”. Being specific makes the action more achievable, thus increasingly the likelihood of it developing into a habit. Secondly, as we saw with Pavlov’s experiments, habits associated with an auditory and/or visual cue are actually easier to maintain. We all know the trapping phone habits that text notifications create, so, why not take advantage of it? Use the reminders app or set a daily alarm if there's a certain habitual task that you want done. More physical reminders like this have proven to be far more effective at developing habits. For instance, if you’re trying to develop this exercising habit, you can lay out your running shoes out by the door: making it a cue in the habit loop!

On the other hand, changing/rectifying a habit is also a completely achievable goal. The best way to change an existing habit is by replacing it with a new one. In the context frame of a habit loop, maintain the same cues, and rather just change the routine. That may sound easier said than done, but if you operate purposefully, consciously, and consistently, you can condition yourself within as little as a week's worth of forcing yourself to do it. Make sure the action is small/specific, easy, and attached to a physical/visual/auditory cue; in far less than the ‘2 months’ that everyone speaks of, you can solidify your habit loop with the power of science.

Incorporating the science of habits into our lives can transform the way we approach personal growth and success. By understanding the habit loop, harnessing the power of habit stacking, and practicing purposeful consistency for a short period of time, we can train our minds for positive change.

Comments